Is Good News on the US Economy Really Bad News? Productivity Numbers Will Decide.

August 04, 2023

Quote of the Issue

“Every high civilization decays by forgetting obvious things.” – G.K. Chesterton

Room Temperature Superconductor Update:

The Essay

↕ Is good news on the US economy really bad news? Productivity numbers will decide.

Journalists have a reputation for focusing on the negative. After all, you never see a “Plane Lands Safely” news headlines. Yet even when I was a full-time news reporter, I always preferred to focus on the positive. In a way, then, this newsletter is a natural fit for my personal preference and natural inclination.

But sometimes good news can be bad news, and I often have to fight my natural bias to see things that way. Take today’s July jobs report. Certainly, it seems like pretty good news all around — news that would seem to point toward a non-recessionary “soft landing” for the US economy.

Perhaps the most noteworthy sign that could be suggesting it’s time to declare “all clear” on the threat of a downturn: Non-farm payroll employment increased by a less-than-expected 187,000 in July after a downwardly revised 185,000 gain the month before, the two weakest monthly gains in two-and-a-half years. The composition of those gains is also encouraging, according to Capital Economics:

July’s gain was heavily dependent on an 87,000 increase in health care & social assistance and a 15,000 increase in government. The cyclical sectors of the economy contributed less than 100,000 additional jobs, pointing to a real economy that, echoing the muted survey-based evidence, is a lot weaker than the pick-up in second-quarter GDP growth suggested.

So what might seem like “bad news” to many Americans — a weakening job market — can be interpreted as good news if you think slower growth is needed to tame inflation. The flip side, however, is that seemingly good news might better be interpreted as bad news.

For example: Wage growth came in at a higher rate than forecast, with a 4.4 percent increase from the year-ago period. That means real wages are growing given a 3 percent inflation rate, as measured by the Consumer Price Index. “Still a sellers’ market for labor,” is how JPMorgan puts it.

Here’s the problem: As The Wall Street Journal explains in its piece on the jobs report, “wage gains exceed both their prepandemic pace and a rate economists believe lines up with low, stable inflation. Fed officials would likely see 3.5% annual wage growth as consistent with inflation near their 2% target, assuming that worker productivity grows modestly.”

That analysis assumes modest productivity growth since the Fed views sustainable wage growth as roughly the inflation rate + the rate of labor productivity growth. And from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of this year, it grew at a 1.4 percent annual rate, the same as over the prior five years. So 2-ish percent inflation + 1.4-ish percent productivity growth gets you that 3.5 percent “sustainable” wage growth number.

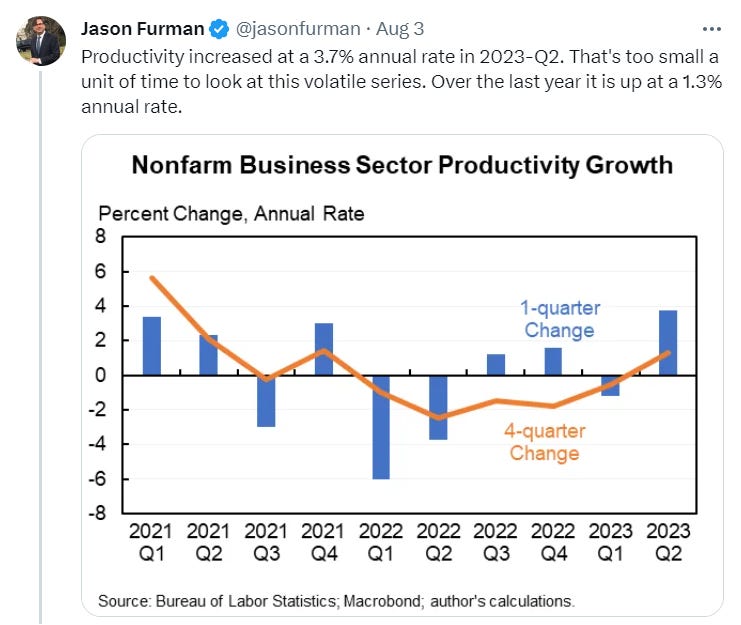

But, but, but … that 1.4 percent productivity number includes a boffo second-quarter report that came out yesterday. Productivity, or nonfarm business employee output per hour, rose at a 3.7 percent annual rate from April through June, the biggest increase in nearly three years. The median estimate in a Bloomberg survey of economists forecasted a 2.2 percent rise. If that Q2 number signals a productivity acceleration, “wage growth of 4 percent is no longer necessarily a deal-breaker for the Fed,” according to Capital Economics.

The big question, then: Are we seeing the start of a productivity boom, perhaps driven in part by the wider and more capable use of AI/machine learning?

Unfortunately, one good productivity number only gets you so far. Quarterly productivity stats are notoriously volatile even without the disruptive nature of the pandemic tossed in for good measure. (Note: JPM thinks we may have another good productivity number in store for Q3 given the tick down in average workweek hours and solid early Q3 GDP tracking.)

That said, this newsletter is devoted to the notion that perhaps more than at any other time in a generation, the technological pieces — though not the public policy pieces — are in place for a long-term elevation in the pace of productivity and economic growth. And it isn’t all about flying cars and space colonies. Faster productivity growth also makes it possible to have faster real wage growth that’s sustainable in the eyes of the market and the Fed. So, you know, faster, please! Let’s make sure good economic news really is good economic news!

5QQ

5 Quick Questions for … policy analyst Neil Chilson on tech regulation

“Big Tech companies have far too much unrestrained power over our economy, our society and our democracy,” write Senators Lindsey Graham and Elizabeth Warren in a recent joint essay for the New York Times. Among their grievances with Big Tech from that essay:

- A lack of legal liability for digital platforms

- Rampant stifling of competition by the biggest players, like Google, Amazon, and Apple

- Misuse of consumer personal data

The solution to this grabbag of digital woes? Graham and Warren propose the creation of “an independent, bipartisan regulator charged with licensing and policing the nation’s biggest tech companies — like Meta, Google and Amazon — to prevent online harm, promote free speech and competition, guard Americans’ privacy and protect national security.” It’s a bipartisan idea, but is it a good one? To find out more, I tapped my friend Neil Chilson.

Neil is a senior research yellow at the Center for Growth and Opportunity. He was previously chief technologist at the Federal Trade Commission.

1/ Lindsey Graham and Elizabeth Warren have proposed a new agency to regulate online platforms. What is the intent of this agency, as you understand it?

It’s hard to tell, actually. The draft statute is a grab bag of everything. It covers antitrust, it covers privacy, it covers national security, transparency, it adds a licensing regime: It’s sort of a wishlist of progressive interventions into the internet sector. I’m not sure what they’re intending to do. It seems like they want to solve all the problems on the internet with this bill.

2/ Senators Graham and Warrren say they only want to “treat Big Tech the way we treat other industries.” Would this bill treat Big Tech like it treats other industries, or would it apply a special level of regulation?

The law is separated into two sections. It applies to dominant platforms, and then it applies to platforms. And it defines “platforms” so broadly that it’s basically every internet service that you might interact with. So the short answer is: No, this would create a special type of regulation for all of the internet, with some more strict rules around the biggest players on the internet. The parallels here are actually more less to general business and more to things like nuclear facilities or something, where you would have a really heavy-handed government licensing regime that could be revoked by the government at any time if you meet certain conditions, which are very broad, such as repeated violations of orders from this commission would be grounds for revocation. This puts—in a way that I don’t think the average business in the US has at all—a really big hammer in the hand of government to swing around and threaten online companies.

3/ Is such a regulator needed?

We have lots of regulators that govern online platforms. I don’t know why we need a new one. The justification for an administrative agency is always that it has some special expertise. And that expertise is usually in one of two things: It’s either special knowledge about the industry or it’s special knowledge about the specific problem that you might be dealing with. We have a Consumer Protection Agency that’s across all industries, but it’s very focused on that specific problem. Or you might have something like the FCC that’s very focused on communications companies and it tries to address all the different types of problems that those companies might have. This regulator would do both. It would cover every single type of problem, and it would cover every single type of company that has a web-based interaction with consumers or with users. Even business users, they’re included too, so I don’t know what company that runs on the internet—or what company generally—wouldn’t be touched by this agency. And they would be charged with solving every single problem. This really looks like a replacement for Congress. Congress is supposed to be the type of general problem solver. And across all industries, if you put this agency out there, they’re basically just a small, less accountable version of Congress.

4/ Is it time for an AI regulator, too, as some policymakers are suggesting?

Again, AI is almost as general as internet. It’s a very infrastructure-level technology, and it means many different things from self-driving cars to recommendation algorithms on your Facebook feed. It’s hard to know what an AI regulator would specialize in. It would have to specialize in that broad set of issues. And we already have regulators that, say, regulate automobiles and driving and know what those problems are like, and agencies that look at things like what might be deceptive if it’s put in your Facebook feed. I think before we do an AI regulator, we would really have to identify what specific set of problems are not being covered by these other agencies and what specific expertise would be needed.

I don’t see any justification for that right now. I would say that this bill, the Digital Consumer Protection Commission Act, is not touted as an AI regulator, but it would be under the definition that it would cover ChatGPT and Anthropic and all of the other pieces of software that are out there. It does contemplate it. There’s a whole definition of algorithms that includes things like generating content. It’s not touted as an AI regulator, but it would be, in fact, that type of regulator.

5/ Just as some people would like to license social media platforms, some would actually like to license these new AI technologies. Is that a good idea?

Even setting aside whether that’s a good idea, the practical difficulties of doing that for software are enormous. There’s a big open source component of AI right now. How would they be affected by a licensing regime? That’s code that can move around anywhere. And I think that type of regime is just practically not very feasible. Another reason it’s not practical is that AI is such a broad term that I think it would essentially sweep in all software. And having to get a license to do software in this country would be a very dramatic departure from the methods that the US has benefited from in the past: letting people experiment, try things, and then test them in the market. And then dealing with any downsides in the future. Software doesn’t fit a lot of the characteristics of things where we might want to have a more prospective approach to making sure something is safe, like drugs or nuclear plants. Software tends to deal with information; it doesn’t tend to cause physical harm, so usually we could mitigate harms later. I think, generally, having a licensing regime for AI would be extremely intrusive, likely to benefit the biggest companies by making it harder to enter the industry, and I think in the end would cut down on the creativity that has driven a bunch of the US software economy.

Bonus: Why do we not default to what seemed to have worked out pretty well for the internet in the 1990s: a light-touch regulatory model?

The proposals are all to replace that default, which AI currently is under, where people can build and test in the market. I think there are two reasons. There are a bunch of people who think, whereas you and I might think [light internet regulation] was a success, that it was a failure. Lina Khan, chair of the FTC, in an op-ed wrote that we can’t afford to do with AI what we did with the internet, essentially, which is let it grow and create trillions of dollars of value. I think that framing is there: People just think the internet is a failure and they don’t want the AI to be a failure as well. I think they’re really wrong about that. And I think if you polled the American people, they would also think they are really wrong about that.

The second thing is that there are calls from some of the biggest companies for regulation in a way that is, to me, somewhat surprising. In the ‘90s, you had some big companies, but they were like the AOLs of the world and the Yahoos of the world. They weren’t out there calling for government to get involved. That does mean there’s a different dynamic. There are a lot of reasons why those companies might be doing that. Some of it is to raise competitive barriers. Some of it is they’re thinking about what AI might look like in 50 years, and they’re worried about it, and they think that the solution to that worry is government regulation somehow. I don’t make all those connections, but I do acknowledge that it’s not pure self-interest. I think all of the biggest companies are thinking 50 years ahead. The problem is when they talk about it to Congress, Congress is sort of thinking, “Well that ‘50 years down the road’ must be here now, and so we should do something now.” And that’s the urgency that you get, say, from the Biden administration.

That’s more of a descriptive take on why it’s happening. I think it’s bad that it’s happening, and I hope that we do stick with the default of permissionless innovation in the software space, which is essential to maintaining both the continued benefits of software and our competitive advantage around the world in creating software.

Micro Reads

▶ LK-99 Is the Superconductor of the Summer – Kenneth Chang, NYT |

▶ Superconductor Breakthrough Claims Traced to Seoul Basement Lab – Sangmi Cha and Jaehyun Eom, Bloomberg |

▶ LK-99 and the Desperation for Scientific Discovery – Tim Culpan, Bloomberg, Opinion |

▶ Fusion Is Having a Moment – Harry Goldstein, IEEE Spectrum |

▶ New superconductor frenzy seems too super to be true – Anjana Ahuja, FT Opinion |

▶ Waymo will expand rideshares to Austin, Texas, its fourth city – Ron Amadeo, Ars Technica |

▶ AI frenzy tests Big Tech’s newfound cost discipline – Richard Waters and Patrick McGee, FT |

▶ The science of forecasting ever more extreme weather – Henry Mance and David Sheppard, FT |

▶ Can big tech keep getting bigger in the age of AI? – The Economist |

▶ You don’t become a science superpower without taking care of the basics – John Thornhill, FT Opinion |

▶ Don’t Blame Canada For Raiding America’s Tech Talent – Editors, Bloomberg |

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars